The Dream of a 40-Hour Work Week

Chef hours have been notoriously extreme for pretty much as long as there have been restaurants. Is that just part of the job or is it a lack of imagination?

A lot of people in the food world are very, very excited about Vyn, for all of the typical reasons that people in the food world get very, very excited. Located on a Swedish hillside overlooking the Baltic Sea, chef Daniel Berlin’s new restaurant, which opened late in October, has gorgeous views and sweeping design. The service is warm and polished. And the food itself is extraordinarily delicious: the cooking sharply honed to let shine the quality of the ingredients, while still expressing clear personality and vision.

But there’s another reason to be excited, an aspect of Vyn that is just as innovative and potentially more influential than anything Berlin might put on the plate: the schedule. The staff at this creative, refined, and above all, ambitious restaurant work only four days a week.

In most other professions, that would hardly be cause for celebration. But restaurants, as we all know, are not most other professions. Even now, well into this season of collective reckoning, when the industry is interrogating and attempting to reform its old ways of doing things, 50- or 60- or 70-hour weeks remain the norm. And in no corner of the profession does that norm seem more resistant to change than in fine dining.

In this issue of Digest, we try to unpack the reasons—some good, some understandable, some totally lame—why work schedules have proven so intractable. And eternal optimists that we are, we also look at a place—like Vyn, and like a small wave of other restaurants around the world—that is attempting nothing short of changing the paradigm.

The view from Vyn (Photo by Jimmy Linus)

How we got here

Long days and longer weeks have been a part of restaurant life pretty much since restaurants began. As far back as 1887, health advocates were describing the normal cook’s schedule as “being deprived of fresh air and sunlight for 14 hours a day.” Things had not improved in 1928, when George Orwell started working as a plongeur in a Paris hotel kitchen, he worked a 14-our shift, six days a week, a schedule that he describes as “exceptionally short hours by the ordinary standards,¨ he later changed jobs and worked with a cook named Boris who toiled from 8.00am until 2.00, seven days a week. “Such hours,” Orwell commented drily, “are nothing extraordinary in Paris.”

In the first half of the 20th century, working hours for most Europeans and Americans shifted, thanks to a lot of labor activism, to a legally-mandated 8-hour day and a 5-day workweek. Restaurants, however, didn’t get the message. If anything, the hours in fine dining only got worse; a 1971 article in the New York Times describes 7-day workweeks and “dawn to midnight” hours in upscale French restaurants (though it did add that fewer young people were being drawn to haute cuisine as a result). By 2009, Ferran Adrià could legitimately congratulate himself on doing better than most other restaurants because his staff “only” worked 5 days a week, even if each of those five days started at 10.00 and ended, with only one 30-minute break in between, after midnight.

Then as now, most restaurateurs explain the situation as one of simple economics. A restaurant has to do a certain number of services for a certain number of covers in order to stay afloat financially, and each of those services functions as its own fixed deadline: both mis-en-place and the dining room have to be set in preparation for it. Hiring more staff to spread the load among more hands eats into margins that are already paper thin. And while it would seem that one could simply raise prices to offset the cost of a larger workforce, many are reluctant to do so for fear of scaring away customers.

Yet not all of the reasons people give for the situation are purely economic, plenty appeal to values and perceptions. One well-known chef who asked not to be named says that even if it were financially feasible to create separate prep and service teams in order to reduce the length of each employee´s workday, such a division of labor would diminish the overall quality in the restaurant. “You need people to be responsible all the way through,” he says. “And you also want them to have the reward of seeing the final dish go out. Without that, they won’t feel the kind of pride in it, and they won’t be as careful that every element is perfect.”

The same chef points out that there are plenty of young cooks who want to work the hours. “They’re super passionate. They’re hungry to learn as much as they can as fast as they can. This is their life. Why shouldn´t they be able to put in as much effort as they want?”

One answer to that question is to think about whether the drive of the few should properly be the norm for everyone else. But maybe we should go even further back and question how it became a norm in the first place. Because there is no doubt that somewhere along the line, the long hours of a chef became not merely accepted, but prized, an internalized sign of dedication and loyalty to the craft. Those 16-hours-a-day, six-days-a-week schedules became, in other words, an ethos.

In the 1970s, a sociologist named Lewis Coser identified what he called “greedy Institutions.” These organizations, like the priesthood or the military (it would take Coser’s wife, also a sociologist, to include motherhood among them), require more from their members than their mere labor; they also require their loyalty and their exclusivity. To cultivate that loyalty, greedy institutions furnish their members not only with a powerful sense of identity, but with a worldview that justifies the sacrifices made to support it, All you have to do is put the institution above everything else in your life.

Coser never explicitly included chefs among his greedy institutions, but the slip-proof shoe definitely fits. There are the long hours themselves, of course, which impede other kinds of meaningful activities and relationships. The expectations that a chef will relinquish the minor celebrations of ‘normal’ human life like weekends and birthdays and New Years Eve. The social life that revolves predominantly around colleagues from your own restaurant. And the ethos that transforms the hardships of the kitchen into proof of its members’ virtue.

In truth, it didn´t require Coser to articulate this; Escoffier himself had already suggested the same way back in the 19th century. The great chef and codifier of French cuisine might be most famous for inventing Peach Melba and establishing the hierarchy of kitchen roles that we call a brigade, but he also established the ethos by which it worked. He banned smoking and drinking and—way before certain Financial Times journalists took note of it—required silence in the kitchen. And he encouraged long hours for cooks as a sign of their passion and a vehicle for building their dedication to the craft.

Escoffier did all this as part of his campaign to professionalize cooking, to distinguish the skilled chef from all those other people (very many of whom happened to be women, but that´s a story for another day) who also cooked. In his quest to prove that chefs were different, he wanted to identify and perpetuate certain shared codes, discipline, and dedication chief among them.

That´s not to say that the passion for craft isn’t real, because if there is one thing that is true about the great majority of people who choose this profession, it is that they do it out of passion. But it is worth questioning whether long hours are the sole or even a necessary way of demonstrating that passion.

The team at Nobelhart & Schmutzig. Photograph by Caroline Prange.

How we get out of here

In the last few years, a small but growing number of restaurants have been asking that very thing. In the process, they’ve begun tinkering with the old formulas that rested on extreme hours. Some, like the Harwood Arms, a Michelin-starred pub in London, have done it by reducing the number of services per day (they got rid of lunch). Some, like Mugaritz in the Basque Country, and Blue Hill in New York, which have done it by reducing the number of days restaurant is open. Some, like Kadeau in Copenhagen, whose staff have actually been on a 4-day schedule for a decade, have recently gotten even more creative, keeping the restaurant open five days a week, but alternating each staff person’s schedule between 3 and 4 days per week for a total of 120 hours maximum per month–and six consecutive days off during the same period.

And then there is Nobelhart and Schmutzig, which is not only reducing schedules, but is also taking steps to educate their clientele on why these changes matter–and what they cost. The Berlin restaurant founded by owner and sommelier Billy Wagner and chef Micha Schafer, has two Michelin stars and is currently 45 on the World’s 50 Best List. And for nearly two years, it has employed a four-day, 40-hour week that has required a near-total overhaul of how the staff works.

Wagner is open about the origins of the change. “We had a sexual harassment situation that came out of a Christmas party for the team,” he says. “And we had no process for dealing with that.” Recognizing that the company needed better structures in place, he and his team began holding workshops, not just on preventing harassment, but also on discrimination, toxic masculinity, and work hours. “All these different topics popped up,” Wagner says. “We started to figure out that they’re all connected.”

In addition to drafting a code of conduct and putting other policies in place, the restaurant cut its staff´s work week down to four days out of the five it was open, and began tracking their hours so that no one went over forty. Making that possible meant hiring four new staff, and to keep costs down, it also did away with one position: the person who worked as steward cleaning the kitchen was promoted to kitchen staff, and his job distributed fairly among the whole team.

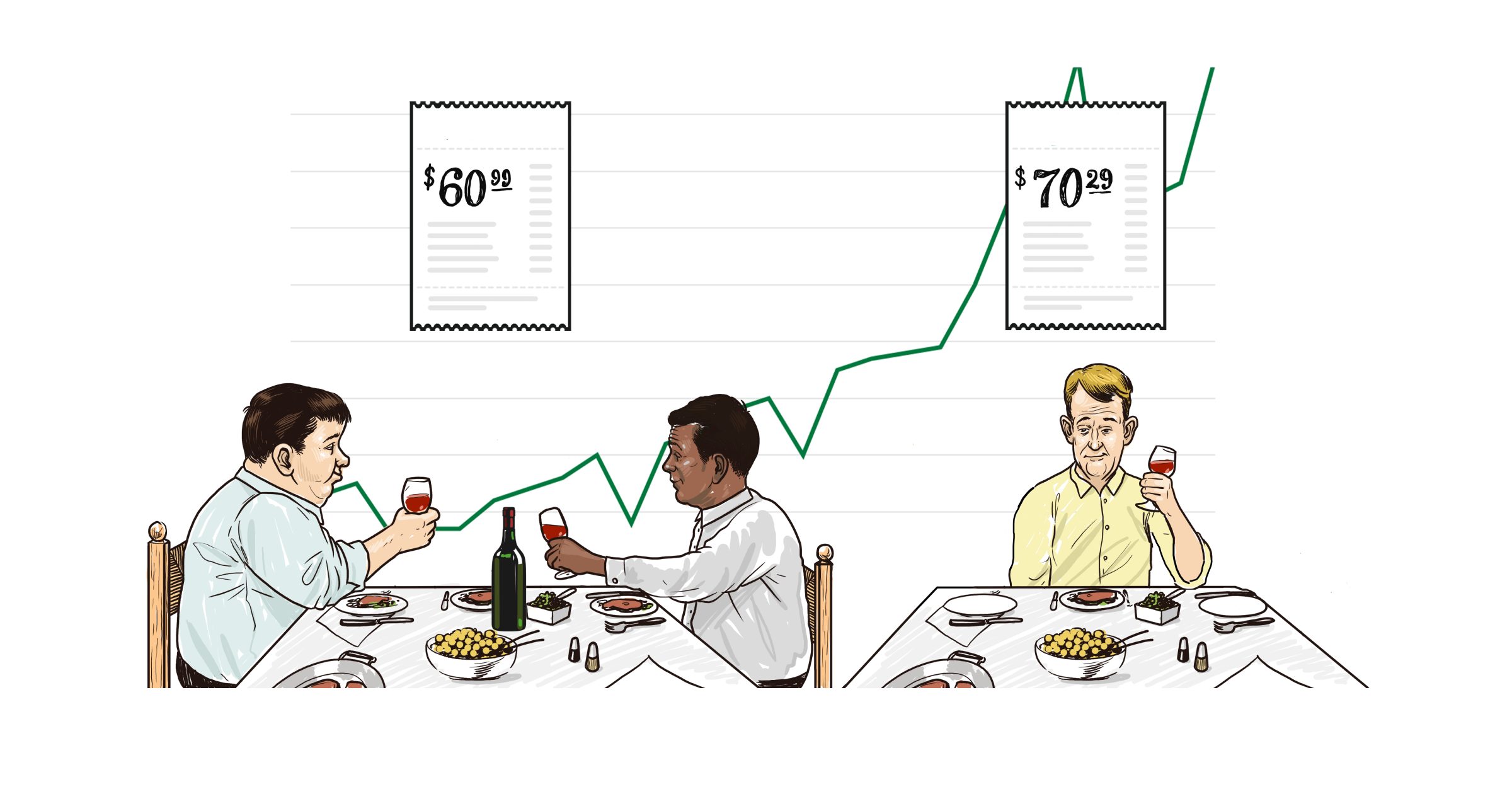

In 2019, Nobelhart and Schmutzig had eight back-of-house staff and one unpaid stagiaire; today it has ten full-time workers plus one part-time and a paid stagiaire. The front-of-house team also picked up a staff member, bringing its total, including Wagner, to five. To cover the costs—an additional 160,000 per year—the restaurant raised prices, and began employing dynamic pricing, charging 175 euros for its tasting menu during the week, and 200 on weekends. “That’s part of the deal.” he says. “If you ask me who’s paying for it, I say it’s the guests.”

He sometimes gets complaints about the price. And he understands why: the customer doesn’t usually know how restaurants work. In Germany (and, let´s be honest, pretty much everywhere) the laws on working hours aren´t always followed; it´s normal for there to be a tacit agreement between employer and employee to ignore the 40-hour limit in favor of 60 or 70. “But the customer doesn´t necessarily know that,” Wagner says. “So we give them the opportunity to learn why the fuck they’re paying 175 euros for a bunch of produce.”

When guests make a booking online, the confirmation email refers them to a page on the website that outlines “what you´re actually paying for,” a list that includes “being a great place to work” with a 4-day week and fair pay. “I’m done saying we´re not too expensive. Now I say the other places are too cheap.” Wagner says.

At the beginning, he also encountered some resistance from a few of his staff who liked the long hours, who saw in that kind of pushing evidence of excellence. But he believed in the change he was trying to implement, and kept pushing himself. ”Personally, I think that the whole way that the gastronomy world has run in the past no longer fits. The young people starting now don´t have the same drive to work 60 or 70 hours, and you have to build your conditions around the way people actually are if you want them feel welcome on your team, if you want them to stay.”

Juliane Herbst, an apprentice at the restaurant, agrees. Instead of barely recovering in time for her next shift, she spends many of her 128 hours outside of work each week seeing her friends and family, and pursuing her hobbies. She looks with skepticism at the ethos of previous generations. “Working long hours is still glorified far too much, and many people make a name for themselves by how many more hours they work than others,” she says. “I think that’s pretty unhealthy. And it doesn’t reflect the spirit of our times.”

The spirit of the times seems to be changing in other places too. At the two-starred Mugaritz, chef and owner Andoni Luis Aduriz recently switched to a four day schedule for his staff after more than two decades of doing it the old way. “I had never done it before because I didn’t think it was possible,” he says. “And then it became impossible not to do.” In addition to reducing the number of days open he divided his staff into prep and service teams and rethought how they work. “No more of this fantasy of a 16-hour-day. Now, the rule is, we don’t do anything that can’t be done in eight hours.*

A similar spirit is in play at Vyn too. Although it is still early days, Berlin expects that structures he has put in place, like only opening four days a week, will enable him to keep his staff´s hours reasonable. But he´s not relying on scheduling alone. He´s also changing the way he thinks about the very food he serves.

At Vyn, a perfect scallop is served charred on one end and raw on the other, an aged partridge breast sits unadorned except for a wafer-thin crisp of its own skin. There are no garnishes here, and minimal ornamentation; the food has been pared back to delicious essentials, and not only for culinary or aesthetic reasons, but for social ones. “We’ve stripped every element from the dish that doesn’t need to be there,” Berlin says. “Just by doing that, we’ve reduced the team’s work week by 200 hours.”

Maybe all of this is a sign that fine dining is changing again, and in ways it never has before. For a few decades now, it has emphasized creativity above all else, questioning every aspect of the traditional meal, interrogating every gastronomic rule, and continuing to push for the new. So it´s always been curious that, despite all that experimentation and liberation on the plate, its practitioners still tend cling to a system for producing that food that hasn´t changed since the 19th century.

But as Vyn and Nobelhart and Schmutzig, and others are making clear, cooking doesn’t necessarily have to be a greedy institution. It´s admittedly a tall order for a restaurant to give its guests excellence and creativity and craft while also giving its staff a decent life and simultaneously managing to keep itself in business. But it’s encouraging that some places are attempting to pull off this hat-trick in ways that restaurants never have before. Isn’t that what we call innovation?

–

Illustration by Jakob Tolstrup