The Carbon Footprint of Eating Out

In 2013, Lucky Peach helped organize our MAD symposium under the theme of “GUTS”. The topics discussed during that two-day event—and later published in a Lucky Peach booklet called GUTS are still as relevant as ever. Every Wednesday until the GUTS run out, we’ll be publishing a feature from the collection. This week, Lucky Peach editor in chief Chris Ying looks at the environmental cost of eating out.

I’ve never seen a forlorn polar bear drifting on a dwindling ice floe, but I have no doubts about the reality of global warming. I think it’s safe to assume that these days not many of us need an in-person ursine encounter to confirm the threat greenhouse gases pose to life on planet Earth.

What’s a bit more difficult is scaling the problem—and the solutions—down to a comprehensible size. It’s hard to grapple with complex, global causes, especially when their consequences, though apocalyptic, reveal themselves only over the course of decades.

But if there’s one place where global warming should feel clearly relevant, it’s the kitchen. Eating, it turns out, is the most significant interaction most of us have with the environment. Even if we remain cloistered in air-conditioned rooms in front of keyboards and monitors for most of the day, at some point we must eat—and whether it’s a carrot stick or a Big Mac, with our first bite we implicate ourselves in the food system, and the food system is responsible for 30 percent of worldwide carbon emissions. That is to say, almost a third of greenhouse gases are a result of growing, shipping, cooking, and disposing of food.

So kitchens connect us to the natural world, and it follows that cooks have a particular vulnerability to the effects of global warming. Seasonal cooking goes out the window when seasons lengthen and contract abruptly and disastrously. There’s also acidification of the ocean, loss of arable land, drought, flood, hurricanes—all concerns for people whose job it is to serve food.

But what role do restaurants play in creating the current environmental dilemmas? What role can they play in a solution? The chefs I’ve spoken to about this have suggested that dining out is terrible for the environment—all those resources being put into procuring and cooking and serving food in such high volume. But so far as I could tell, nobody (outside of certain large restaurant chains) really knows much about the environmental impact of their restaurants. It reminded me of the way I refuse to look at a scale when I know I’m particularly overweight—better to accept the problem and move on. That doesn’t seem quite good enough, though, when we’re talking about the future existence of the natural world.

Overall environmental impact is difficult to distill into a number or grade; there are too many moving parts to declare something absolutely good or bad. For example, efficiency is a key to conserving resources and, in many cases, reducing carbon emissions, but efficiency might be achieved in any number of otherwise questionable ways: pesticides, antibiotics, brutal animal treatment, genetically modified crops. The endlessly intertwined nature of nature is part of what makes environmental change so unwieldy and seemingly unapproachable.

A friend of mine named Peter Freed works for TerraPass, a respected San Francisco company that deals in emissions reductions and renewable energy projects. I asked Peter if he could help me measure the total environmental impact of a restaurant meal, and his answer was no, he couldn’t—there are just too many moving parts. What he could do was assess the greenhouse gas emissions of a meal and, by proxy, the culpability of restaurants in global warming.

Our starting point was the assumption that restaurant dining is fundamentally bad for the environment—or, more specifically, that restaurant dining is worse than cooking and eating at home. So we’d have to compare the carbon emissions of a restaurant meal to a similar meal prepared at home. Prime Meats in Brooklyn struck me immediately as an apt choice for the former. Much of their menu is doable—if not exactly replicable—for a home cook: chilled iceberg salad, Caesar salad, roasted beets and carrots, ricotta dumplings, grilled pork chops, pork schnitzel, steak frites, burgers. In other words, dinner at Prime Meats is something that you might weigh against staying in and cooking for yourself.

Restaurants in the Prime Meats strata have the most to lose if home cooking does turn out to be an earth-cooling alternative to patronizing neighborhood restaurants. But the two chef-proprietors, Frank Falcinelli and Frank Castronovo, consented to the study without hesitation.

Not all restaurant menus, however, lend themselves as easily to a showdown with home cooking. I don’t think anyone has ever puzzled over whether to stay in or have dinner at Noma. One might question the value of comparing the carbon emissions of a twenty-three-course tasting menu that counts lichens and insects among its ingredients to that of a weeknight lasagna. But what makes Noma an interesting case study is its reputation. Much of Noma’s allure is tied to the restaurant’s commitment to local Scandinavian ingredients, specifically plants and animals foraged from nearby forests and beaches. Foraging is a buzzword that comes fully loaded with positive connotations. If a chef forages, he is engaged with nature, and therefore he cares about nature and does his best to be environmentally responsible on the whole. This is the type of extrapolation the mind makes when we hear terms like organic, sustainable, free-range, cage-free, hormone-free, non-GMO, seasonal, local, green, natural, wild, raw, fair-trade, homemade. Each implies the others and is a convenient signifier for “environmentally sound” the same way that light, fresh, low fat, and whole grain connote “healthy” whether or not what they’re describing is, in fact, good for you.

Many people—myself included—take it on blind faith that a small, localized food system is definitively better than a large-scale one. Testing this assumption against detailed data on a restaurant that specializes in small-scale seemed like a worthy pursuit. Again, I was impressed and encouraged when René Redzepi and the board of directors at Noma agreed to be part of the study.

So Peter and I settled on a life-cycle analysis of three distinct meals. What we were after was a single number for each: the kilograms of carbon-dioxide-equivalent emissions (CO2e) produced by each meal—the meal’s carbon footprint.

A full life-cycle analysis examines the total environmental impact of a product, from raw material to used item. For instance, if we were to analyze an egg, we’d look at everything that went into the care and raising of the chicken that laid the egg (what it ate, how the feed was grown, how the feed got to the farm); the transportation of the egg from the farm to the distributor, to the store, to the consumer; and whether the shell was composted or simply discarded. Such an analysis can run hundreds of pages, the product of thousands of hours of research.

Ours was more like a life-cycle analysis lite. Peter described it to me as not looking at this egg, but looking at an egg. In other words, we’d be specific where possible—looking at actual power and gas bills, and real delivery schedules—and generalizing where necessary. Rather than looking at the actual berries used at Noma, we’d use publicly available information on fresh berries from Nordic countries.

The six areas we examined were:

Deliveries, including the frequency and size of trucks bringing food and supplies to each restaurant. In the case of the home meal, we looked at the emissions associated with driving to the grocery store and back.

Foraging, including the size of the car used by Noma’s house foragers and the distance they traveled each day. (There was no foraging involved in the Prime Meats or home meal.)

Electricity use.

Other energy use, specifically natural gas.

Waste breakdown and hauling.

Ingredients, meaning the emissions associated with the cultivation and/or production of the raw vegetables, meat, and pantry items used in every dish.

The menus for the three meals examined were:

Home-cooked meal:

Ribeye with roasted potatoes

Radish and parsley salad

Peach and almond crumble with whipped cream

Prime Meats:

Steak frites

Escarole salad

Crème brûlée

Noma:

Fermented gooseberries as olives

Nordic coconut and bouquet

Crispy reindeer moss, ceps spice, crème fraîche

Flatbread and grilled roses

Peas in a pod

Tender pea tendril with wild strawberries

Black currant and roses

Pickled quail egg

Cod liver and crispy sweet milk

Aebleskiver

Leek and cod roe

Grilled vegetables, berries, and buttermilk

Raw shrimp and ramsons

Onion and pear stew

Caramelized cauliflower and whipped cream

Potato and caviar

Turbot and greens

Blueberry and ants

Potato and plum

Beet

Yeast and skyr

Seaweed danish

Pork skin and dried berries

I should admit that I was hoping for a particular result. I was fairly certain that Noma’s emissions factor would be far higher than that of the other two meals—there were just too many ingredients in the Noma meal for it to be comparable. The way I looked at it, there were three possible outcomes for the home-cooked and Prime Meats meals: Prime Meats could be vastly worse, slightly worse, or slightly better than the home-cooked meal. Any of the three results would provide useful information; knowing where we stand is the only way to take a step forward. But if the two were close, that’d be a real coup. It’d be much easier to spur chefs to action if I could tell them that they were within reach of saying, “Eating at my restaurant is the best thing you can do for the environment.”

Peter and I presented the results of the study onstage at this year’s MAD conference, in front of the Franks and René. None of them were aware of the results ahead of time. When we revealed the numbers, all three chefs spun around and craned their necks to see the monitor behind them, again impressing me with their curiosity and openness. There was no real incentive for them to subject themselves to this sort of scrutiny, let alone stand onstage with no idea what we would reveal about their restaurants. At times, the modern restaurant business can revolve frustratingly around lists of whose restaurant is the best, but here were three chefs who were more concerned with how they could just do good.

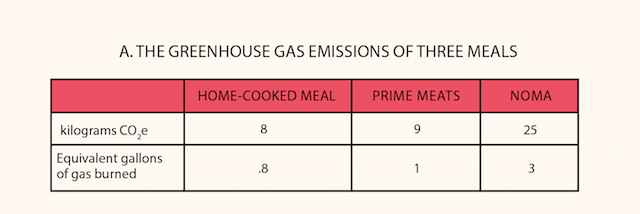

A meal at Prime Meats produces 13 percent more greenhouse gases than a similar meal cooked at home. A full tasting menu at Noma accounts for approximately three times more emissions than a home meal. (Figure A) You’ll notice I’m carefully avoiding saying that Prime Meats is worse than a home-cooked meal or that Noma is worse than Prime Meats. These are raw results, and I’d argue that they are neither the most important nor most interesting results of the study. But they’re a good starting point for narrowing a broad and complex problem down to a simple, understandable figure. Take a look down between your feet and watch the arm on the scale swing and bounce to a stop a few pounds farther than you hoped it would, and take a breath.

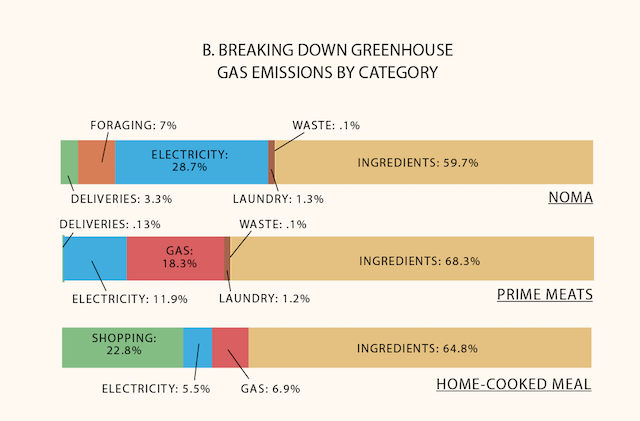

Figure B is a breakdown of the emissions of each meal. In all three instances, 59–68 percent of the greenhouse gases are a result of the ingredients themselves—a useful consistency. The home-cooked meal contained seventeen ingredients, Prime Meats used sixteen, and Noma four hundred, but as a portion of the total emissions of their respective meals, the ingredients’ contributions were all within the same 9-percent range.

The carbon footprint of different farm practices is critical, but changing the way ingredients—organic or otherwise—are grown or raised is a bit beyond the reasonable control of most restaurants and diners. I’d expect it’s also a deal-breaker to ask chefs to alter their recipes, and even if they were willing to do so, it would be a leaky solution. For the moment, let’s discard the idea of omitting or changing certain ingredients as a way to reduce carbon emissions. Where we want to look for possible fixes is in the other 32–41 percent: the overhead.

Prime Meats’ and Noma’s energy usage produce almost the exact same emissions in a given week and account for about the same percentage of the restaurants’ overall carbon footprint. The per-meal emissions at Noma are much higher because Prime Meats serves 1,350 people per week, while Noma only serves 450.

These insights are essentially just reverse-engineering a large-scale food system. There’s a reason why industrial agriculture came about: we needed to feed a growing population cheaply and efficiently. There are plenty of good reasons to criticize the consolidation of food production to a small group of corporations—but efficiency is not among those reasons. If we limit our concern to global warming, one wonders if it’s really better to have twenty different farmers each deliver broccoli in their own trucks to the farmers’ market, compared to one veggie-packed truck delivering to multiple grocery stores.

Again, we’re only looking at one aspect of environmental impact—there are many other factors to consider. This idea is most clearly demonstrated by the data we gathered on Noma’s foraging. Noma’s foragers drive a Volkswagen Caddy Maxi Life camper van 250 kilometers per day in pursuit of elderflowers, Spanish chervil, roses, pine shoots, chamomile, strawberries, black currant shoots, juniper, wood ants, ramson, rhubarb, apples, dandelions, fiddlehead ferns, rocket, yarrow, swamp cress, etc. The van’s emissions make up around 7 percent of the restaurant’s total carbon footprint, or 777 kg CO2e per week.

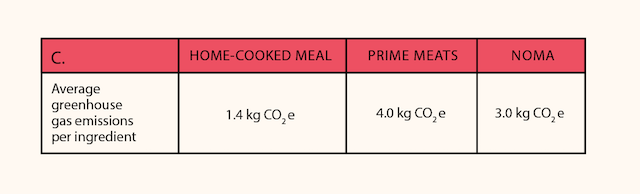

Does that mean foraging is an environmentally detrimental practice? The question is academic. Noma’s not going to cut its foraging program, and that’s almost certainly a good decision. Foraging reduces dependence on commercial agriculture, and there are immeasurable gains to be had by improving our familiarity with the ecosystems around us. No resources go into planting or cultivating a foraged ingredient, and in fact, foraging actually helps lower the average emissions per ingredient at Noma. (Figure C)

The abundant positive effects of foraging make the question of whether or not to forage an easy choice, but it’s useful to know the emissions it generates. After our presentation, René’s wife, Nadine, came up to Peter to say she’d been insisting for some time that the restaurant buy a more fuel-efficient foraging car, and to thank him for making the case for her. If they were to make that switch, the emissions factor of foraging would drop to zero.

Three things I’ve learned that are worth sharing:

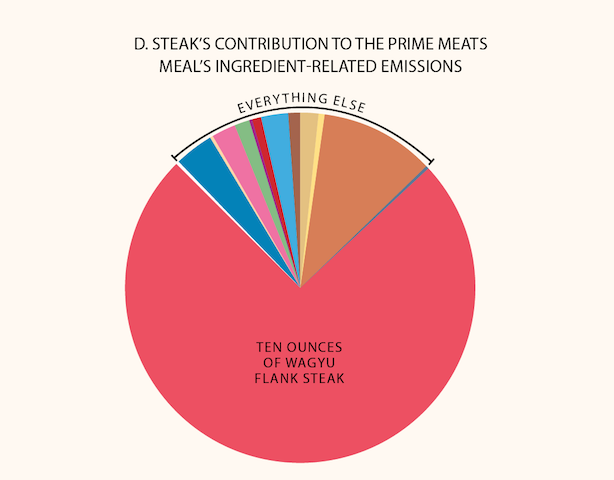

1. Meat is by far the worst, emissions-wise. (Figure D) Earlier I said that it was moot to expect cooks to avoid certain ingredients for the sake of global warming, but I admit we played a bit of a reverse gambit in choosing our menus. Knowing that twenty-three courses at Noma were always going to leave a larger footprint than a three-course home meal, Peter and I evened the playing ground slightly by choosing steak for the home-cooked and Prime Meats meals. Raising beef cattle is a resource-intensive endeavor and methane emissions from cow flatulence and manure is actually a major contributor of GHG emissions. The ribeye in the home-cooked meal accounted for 84 percent of the ingredient-related emissions. At Prime Meats, the wagyu beef accounted for 74 percent.

2. In 2012, 40 percent of the electricity supplied by Dong Energy in Denmark was produced by coal. That’s why the power grid in Copenhagen is so much dirtier than that of, say, California (7.5 percent coal). The staff at Noma discovered this while putting their energy bills together for TerraPass. It took them by surprise, and as we were assembling the study, they emailed to say that they’d elected to switch to a 100 percent renewable energy supply (at an increased cost). If that change goes through, their yearly emissions drop instantly by 29 percent. In the words of GI Joe, knowing is half the battle.

3. Whip-its are bad for the environment, too. In an act of undeniable laziness, when I was making whipped cream for the home-cooked dessert, I elected to use a nitrous-oxide siphon rather than whipping the cream by hand or with a machine. Later, Peter called to tell me that the global warming potential of nitrous oxide is somewhere in the range of 300 times worse than carbon dioxide, and that the two nitrous cartridges I used had a larger carbon footprint (8.7 kg CO2e) than the entire meal (7.5 kg CO2e). We didn’t factor this into the study, to avoid skewing the final results, but I feel compelled to admit it. Efficiency takes elbow grease.

So, let’s dispense with the idea that eating at a restaurant is inherently bad for the climate. Prime Meats is within striking distance of matching the carbon footprint of a home-cooked meal. Just for kicks, I asked Peter what TerraPass would charge to fully offset the annual carbon footprint at Prime Meats (about $0.11 per diner) and Noma (about $3 per diner). There are, of course, plenty of ways to improve the efficiency of a restaurant without forking over money for offsets—installing LED lightbulbs in spaces which require task lighting; consolidating deliveries (Prime Meats only takes eight deliveries per week); using more energy-efficient refrigerators, coolers, ovens, and fan hoods.

And what about Noma and restaurants of its ilk? To look at the raw numbers and say that dinner at Noma is an inefficient meal would be like saying a visit to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa is an inefficient way to see a beautiful woman. Noma serves a different purpose. In any creative field, there will be individuals that push us to reconsider the status quo. The study itself was a response to an opportunity presented by René Redzepi and Noma via the MAD symposium. And, just like Prime Meats, Noma was eager and thorough in volunteering every bit of information requested of them.

The pie-in-the-sky end game for all this introspection is a consortium of concerned restaurants that are willing to face the problem and take active steps toward solutions. Imagine a group of restaurants that agreed to: 1) open themselves up to a full examination of their respective carbon footprints, and 2) commit the necessary money, time, and on-site improvements to reduce their carbon footprints to zero. The money would be pooled together to further study of restaurant emissions, develop a list of best practices, and pursue food-related emissions-reduction projects. If a few influential restaurants sign on, their participation makes participation desirable, and before you know it you’ve got a branded strain of do-gooding. Carbon-neutrality becomes something that benefits your own restaurant as much as the planet. Simple.

I’m being naïve, but maybe not as naïve as you think. Diners are increasingly considering their personal ethics when deciding what and where to eat. Why not capitalize on it? More importantly, why not make the same sort of choices as chefs? What kind of restaurant do you want to be? What sort of work do you want to do? A few brave chefs could spark a movement that transforms dining out into an act of purposeful good.

Restaurants are among the most agile, innovative small businesses on earth. They are a place where creative thinking about efficiency happens every day—whether it’s making the most delicious things with the cheapest cuts or fitting all your mise en place into the low boy. There’s no reason why they couldn’t or shouldn’t be leaders in environmental stewardship.