Ben Shewry Goes to Canada

In Canada, dessert is everywhere.

In the winter of January 2014, I flew to Ontario with my wife Natalia and our children Kobe, Ella, and Ruby, leaving behind us a family holiday filled with Californian cultural icons, including Jurassic-sized turkey legs at Disneyland, nachos with cheese sauce at the Staples Center, secret menu items with hidden biblical messages at In-N-Out Burger, and, of course, the fuel of the Los Angeles working man: tacos. We arrived to sub-zero temperatures at Toronto’s Pearson Airport.

We were in Canada as guests of the Stratford School of Chefs, an elite little institution in the beautiful, wee town of Stratford, Ontario. It’s a place run by people who really give a damn about genuine hospitality, proper food values, and the brilliant young people they teach every day.

I was there to teach the students about what it means to me, both physically and philosophically, to be a chef. Each night, over the course of a week, we prepared five dinners for forty guests. Facing this task and being 16,127 kilometres away from my battle-hardened, talented team of kitchen warriors at Attica was both disconcerting and exhilarating.

Many of us chefs are a controlling bunch. We like to spend all day picking thousands and thousands of very small, very annoying little leaves and itty bitty flowers, and doing other minuscule, downright maddening tasks that most fully rational folk would never even consider. But no, not us. Like flies and spiders hopped up on meth and caught in a never-ending web of craziness and self-gratification, we are constantly “seeking perfection,” whatever the hell that means.

But with six or so young cooks in just their second year of professional cooking by your side, you can throw all notions of “seeking perfection” out the window. As you should. The point of my being there was to inspire and show these great young people the way I view the world through food. It wasn’t about trying to recreate Attica, an Australian restaurant with a culture and ingredient set to draw from that are very different from Canada’s.

Over the years, I’ve learned that I gain the most from traveling when I am able to take in the surroundings with a fresh set of eyes, without forcing all of my ways of operating into the situation.

So I entered the experience prepared and well rested after three weeks of California hamburgers and NBA Basketball. My mind was open to the many culinary possibilities of the great region of Ontario and its people, and I was free from the dishes we cook each day at Attica — no potato cooked in the earth it was grown, no kangaroo, and no infuriating miniature beehive desserts.

My friend Mike Booth picked us up from the airport, and we began our journey towards Perth County, leaving behind Toronto’s winter grime of snow, dirt, salt, and slush. The countryside opened up to endless fields of the whitest snow.

I began to smile the kind of smile I’ve had since childhood. It’s the smile that would get me into trouble with bullies in the playground, the slightly smug smile that comes in both times of discomfort and in times of inspiration. Mike glanced at me and asked, “What’s so funny, Ben?” My response was, “Mike, everywhere I look, I see dessert!”

When we arrived at our cozy lodgings in Stratford, we were humbled by the great party our friends from the local culinary community had welcomed us with. There was charcuterie lovingly hand-crafted by chef-instructor Neil Baxter of Rundles Restaurant, as well as beautiful breakfast care package from the amazing Lass family of Churchill Farms (in my opinion, they run one of the most ethical and high quality farms in the world). It was especially nice to use the time to catch up with my friend and former Attica team member Ryan O’Donnell, who is now a chef-instructor at the school.

With Mike Booth

Leaving my family well-settled, Mike, Ryan, and I hit the road in search of the winter bounty of Perth County. But as any salty road tripper knows, you’ve got to have a supply of semi-illicit consumables to energize yourself through the hardest and coldest moments of the journey.

So, before heading out of town, we stopped off at the local hero Revel Caffe to load up our gnarly seven-seat people mover with the best goddamn croissants I’ve ever tasted. In fact, they should be outlawed, or maybe their creator chef Randi Rudner should be arrested by the gendarmerie, for humiliating French pâtissiers the world over and etching a memory into my mind so crystalline that I was able to think of nothing but those crossaints for weeks.

Loaded full of yeasty dough, we headed off to visit my old friend and kindred spirit, the renowned farmer, musician, and artist Antony John of Soiled Reputation. A visit to see Antony for me is an almost religious experience. His wealth of knowledge of the land and how to care for it, and the way he provides wholesome, delicious food for hundreds of people in Ontario, is inspiring. It’s unusual to find a creative person who can manage to articulate their vision for ethical farming and get meaningful work done in the process.

After raiding Antony John’s mind and root cellar, we headed over to the little village of Shakespeare to visit Shallot Hill Farms, owned and cultivated by James Harrison. As we arrived, James was bottling the last batch of his maple syrup, which is boiled down in a little sugar shack from hundreds of liters of sap gathered by tapping the maple trees in his stand.

Small batch maple syrup is incomparable to the commercially produced stuff we get in my part of the world. Think of how a salad would taste if you dressed it with two-week-old deep fryer oil instead of that walnut oil that was cold-pressed two weeks ago by the farmer down the road. That’s the difference we’re talking about.

I’m kind of a purist when it comes to maple syrup. Years ago, I was stuck in a log cabin in a snow storm for fifteen minutes with nothing but a three-liter bottle of liquid gold to keep me warm. So, in the interests of self-preservation, I decided the only way to survive the storm would be to have small nips of the syrup — straight up, neat. Needless to say, the bottle of maple syrup came off second best that day, and I lived to tell you this tale. Maple syrup: the drink of straight edge folks the world over.

As we said farewell to James, a thought crossed my mind. I asked him if we could add a maple branch to our order. James, being the straight shooter that he is, didn’t raise an eyebrow. Instead, he walked across to his sugar bush, chainsaw in hand, and trimmed off a branch. Things were coming together nicely, in a deep winter kind of way.

Mike put the pedal to the metal, and we raged across the countryside in our Grand Caravan towards the town of Kitchener, where I begged Mike and Ryan to stop at a local Chinese restaurant so I could try the “Cold Potato Sticks” we’d seen advertised in the window. “Come on, guys! I know its -10C out, but that’s perfect weather for cold potato sticks.”

As day turned to night, we cruised back to Stratford, slightly bloated from the raw potato but fulfilled by our day’s work. I was looking forward to getting into the kitchen with the students and my old friend chef Brian Steele, a senior instructor at the school.

The first couple of days we ran a menu of dishes inspired by the brilliant people I had met on the trip.

“Antony John’s Winter Sunflowers” was a nod to several things: the man himself and the fact that I was cooking with Jerusalem artichokes stored in his root cellar while at the very same time Jerusalem artichokes were beneath the ground in Australia, giant sunflowers towering over them.

“Potatoes Grown by a Decent Man” paid homage to farmer James and his no-bull, let the quality of the ingredients do the talking attitude.

“Onion Jewels and Ruth’s Fine cheese” was prepared in honor of environmentalist and epic cheesemaker Ruth Klahsen, owner of Montforte Dairy.

But I saved the dish I was most looking forward to creating for the end of the week. It required snow. Plenty of snow.

My buddy Mike, master of procuring all my culinary playthings, had been put in charge of making sure it snowed on Friday and Saturday. He was under the pump, as it was now Wednesday. It hadn’t snowed for four days and the snow outside the restaurant was dirty, icy, and, in a few designated patches, yellow.

The daily banter went something like this:

“Ben, I got that maple sugar you asked for.”

“That’s great, Mike. But I need snow, man!”

“But I got the ten kilos of sheep’s milk yogurt you asked for.”

“Mike, we need snow, mate. I don’t care what you gotta do, but it’s on you. You gotta make it snow, and I don’t wanna hear any lame excuses, you understand?!”

Sitting around after Wednesday night’s service, eating maple taffy (that’s maple syrup boiled to 235.F and poured into snow) and trying to workshop my idea for a dessert based on snow, I asked Mike and Ryan what Canadians really like eating besides maple syrup. Their answers mostly boiled down to bacon and whisky.

There must be something else, I thought. They assured me that wasn’t the case. Well, to the suggestion of bacon in a dessert, I’ll borrow the famous line from former NBA great shot blocker Dikembe Mutombo: “NOT IN MY HOUSE.”

Whisky, on the other hand, is a different matter. Mike explained that his family has a proud tradition of making whisky and that his great, great, great, great, great, great grandfather Joshua Booth was a 18th century miller, distiller, and politician who made 100% rye whisky on his farm in Millhaven, Ontario.In the 1990’s, his father, himself a master distiller, had recreated the family whisky and named it Lot 40, after the spot where his ancestors originally made their rye whisky.

As Mike was telling me about his family history, I looked up at the large jar of maple butter (think of the texture and consistency of creamed honey, but made from pure maple syrup) sitting on the shelf above us. We decided to mix that into a bowl of fine local cream and then hit that bad boy with plenty of the Booth family whisky and a little extra toasted, ground rye. We leaned over the bowl and took a moment to breath in the fumes before tasting the sweet Canadian nectar.

It needed a pinch of salt and a splash more whisky, and that was that — smiles all around. Sometimes the great moments of creativity in your life come from collaboration and sharing a process with others.

Waking early the next morning, fresh dessert covered the ground, the roads, the trees, everything. Damn, there was so much freshly made dessert on my driveway I had to get out the shovel just so I could leave the house. My nine-year-old son Kobe (who obsesses about basketball the way I obsessed about cooking as a child), Ryan, and I were meeting up with some other chef buddies at the YMCA for a few games of pickup basketball. Ryan and I battled hard against the sharp shooting, highly annoying midget (Kobe) and his pickup 6’5 team mate, Mr. “Oh, I haven’t played in years, not since it was my job.”

Licking our wounds after a thorough beating, having played to the classic, no blood, no foul street ball rule, Ryan and I dragged ourselves to the local food co-op for a soul restoring Mennonite Country sausage sandwich.

Back in the kitchen that afternoon with the students, we bragged about how we’d “kicked arse.” Talk is cheap when the 6’5 man isn’t around.

A couple of quick hours of prep with the students and we had the mise for the night’s dessert in front of us. I stood around the bench with the skeptical young Canadians (“Come on, dude, snow isn’t cool.”).

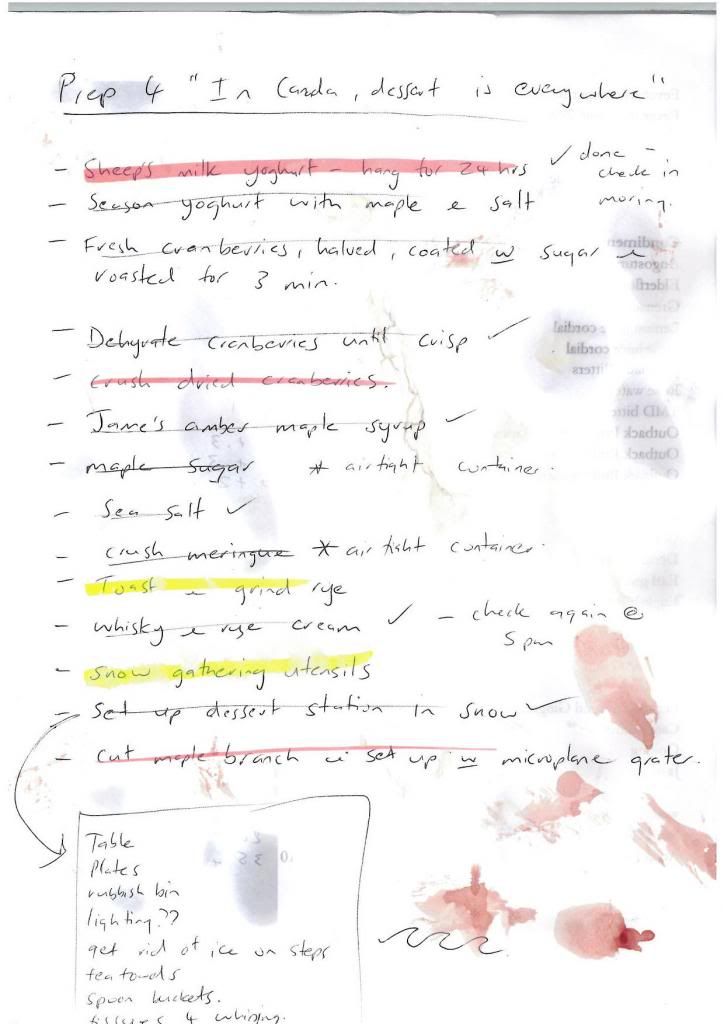

Here’s the prep list:

My instructions:

“So, guys, this is how it’s gonna go down. Pass me a frozen bowl, please.”

“We will place a dessert spoon of the sheep’s milk yogurt in the middle of the bowl, like this.”

“Then the roasted cranberries. Jordan, can you run outside and get the snow please, mate?”

“OK, now the snow on top of the cranberries — at least four kitchen spoons full. We have to go fast now, guys.”

“Now, let’s sprinkle the maple sugar on the snow so the maple syrup has something to adhere to.”

“Plenty of the maple syrup. Now, the crushed meringue and dried cranberries, and then the salt.”

“Next, we grate a little fresh maple bark over the top, and let’s pour the whisky cream over the whole thing. I think we need a lot of that bad juice.”

After plating, the moment of truth was upon us — that delicious moment of uncertainty when you’re about to find out if you’ve succeeded or failed. This moment determines whether the last thirty minutes before service will be mildly relaxed or extremely unpleasant, with the team having to run about the kitchen frantically trying to make a terrible dish good.

I had the first mouthful, smiled, and stepped back to let the students dig in. “What do you think”, I asked. “Is it any good?” Their reaction was pretty cool, and I think they were surprised. “It tastes like Canada,” one of the students said. “I never knew snow could taste this good.”

The texture of the dessert was remarkable. The fresh snow was so unbelievably light and unlike any trendy “snow” that we trendy chefs ever make. The irony was not lost on the team as I explained that in recent times, chefs the world over have tried to replicate natural snow in their kitchens, but that there really was nothing quite as amazing as the real deal — precipitation falling from clouds, from at least 500 feet, in the form of crystalline water.

I had one more little surprise in store for both the students and the guests. The restaurant’s dining room is situated around a beautiful snow-covered garden that all the tables look out onto.

From the moment I first saw it, I knew we had to do the dessert service outside, in the snow. “Let’s bring the snow to the people,” I told the team.

So we quickly set up a dessert station under a tree in the courtyard of the Old Prune Restaurant.

We battled through service, and after the last savory course was completed, we ran out into the knee-deep snow to looks of bemusement and horror from the guests.

We began to serve the dessert with reckless abandon, as one can’t be too precious when plating desserts outside. I would yell to Jordan, who was in charge of the mise, “We need fresh snow!”, and he would trudge off to a pristine corner of the garden and scoop up enough for the round of eight in a large bowl with a Chinese wok chan (an important implement for snow collection).

By this point, the whole restaurant was going kinda crazy — one massive party, with guests coming outside to see what we were doing, and lots of laughter in the dining room at the spectacle of chefs and waiters frantically grating maple bark and pouring whisky cream tableside.

At the halfway point of dessert service, when we began to lose the feeling in our hands, I realized I’d made a serious mistake. It was -18C outside and I was plating the dessert in a t-shirt. Regardless, we joked about how we could use a Saint Bernard and some brandy about now, and pushed on toward the finish. All in, we’d spent twenty-five minutes out in the cold.

On a natural high from the excitement in the dining room, we rushed back into the warm kitchen, and it was then I realized it’s not smart to spend twenty minutes in the snow at -18C in a t-shirt.

A day later and I was as sick as I’ve ever been.

With Brian Steele and some of the students.

As we departed Stratford the following day, bound for Melbourne, I thought about how amazing a place Canada is and how hard it must have been for my Ontario-born grandmother Elaine Shewry to leave when she migrated to New Zealand after marrying my grandfather Bob Shewry in 1943.

As pretty as Canada is in winter, it’s the spirit and beauty of the people that inhabit it that give the place its soul. As we made the long journey home, I thought of the words of 18th century German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe:

“The world is so empty if one thinks only of mountains, rivers and cities; but to know someone who thinks & feels with us, and who, though distant, is close to us in spirit, this makes the earth for us an inhabited garden.”

And that’s how I feel about Canada.