Hospitality workers are uniquely susceptible to alcohol abuse. Can that change?

This summer, Ferhat Dirik took two monumental steps. First, he quit drinking. Then, he told everyone about it.

Together with his brother Sertaç, Ferhat has transformed Mangal 2, his family’s already popular ocakbasi, into the kind of place with its innovative take on Turkish cuisine and a strong natural wine list, that regularly gets labeled a cult favorite. But for all the success, Ferhat, who is the restaurant’s manager and creative director, was himself not doing so well: drinking more and more heavily, blacking out more and more frequently, and feeling more and more shame the day after.

On June 25, he stopped by a pub with a friend for what he intended to be a quick pint or two before returning to work. “Sadly, as an alcoholic,” he wrote, “Things often don’t pan out that way.”

Five Guinnesses in, he had forgotten about work and was stubbornly arguing with the pub’s owner. The next day, hungover and mortified by his behavior, he found himself reaching a decision he had never been able to take before. “There had been two or three years where I wanted to quit, but there was always a reason not to,” he says. “But the degree to which I was becoming blackout drunk, and the degree to which I was having very negative thoughts was accelerating. After my last episode getting really drunk, I was just like, I don’t want to feel this way ever again.”

Twenty one days later, and still at the very start of his sobriety, he wrote about his decision in Mangal 2’s newsletter and was stunned to receive an outpouring of support. “I had 80 or more people writing me, most of them strangers, saying how the newsletter and my experience resonated with them,” Ferhat says. “Getting blackout drunk, completely losing my memory, and all the self-loathing after—I had thought that was unique to me. But now I learned that my experiences were quite common. It made me feel—not good, because it was hard—but at least better. Like I’m not the only one with these struggles, I’m not the only one with these flaws.”

He is definitely not alone. In fact the hospitality industry is notoriously vulnerable to alcoholism and other kinds of substance abuse. Chefs are nearly twice as likely to be addicted to alcohol and drugs as the wider population, and far likelier to die from it: 1.77% times more likely for cooks and 2.33% for bartenders. In the US, 9.5% of the general workforces suffers from substance abuse disease (which encompasses both alcohol and drugs), while within hospitality, the rate is 16.9%–the highest of any industry.

Many factors contribute to that distinction, from the long hours and high-pressure atmosphere to the prevalence of alcohol within the culture of hospitality and the fact that the work itself often draws people who are young and still finding their way. And, as Ferhat puts it, “Because of the hours, by the time you get off, the only place that’s open is a bar. You’re kind of almost set up to fail.”

He himself first began drinking as a pre-teen in part, as someone who grew up in a restaurant, alcohol was so closely woven into hospitality, and as he grew up and continued to work in the industry, his whole identity. “There are many more anecdotes, all negative, when I tie in getting drunk with my working life,” he writes. “The two intertwined like hell and fire.”

Yet increasingly, the industry itself is admitting it has a problem. Prominent chefs like The Hand and Flowers’ Tom Kerridge, bartenders like Dead Rabbit’s Jack McGarry, and sommeliers like elBulli’s David Seijas have all spoken openly about their addiction and recovery, and a number of organizations have sprung up around the world to help both employers and employees address it. “Something is happening,” says Mickey Bakst, retired manager and maitre d’ of the acclaimed Charleston Grill in Charleston, South Carolina. “There’s been a major shift towards the taking care of employees, their wellness and mental health. And substance abuse is unconditionally one of the most serious mental health issues in the industry worldwide.”

One ocean and half a lifetime away from Ferhat, Mickey, who spent 50 years in the industry, is also part of that growing movement. Together with co-founder Steve Palmer, he created Ben’s Friends, a non-profit organization that works specifically with hospitality professionals struggling with alcohol and drug addiction. Both men have been sober for decades (41 years in Mickey’s case; 25 in Steve’s), and they’ve seen first hand the devastation that addiction can inflict. “A number of years ago, we started getting together every Saturday morning, and every Saturday morning we found that we were talking about another kid in our industry who had destroyed their lives, ruined their careers, and in many cases, lost their lives.” They founded the organization in 2015 in the immediate wake of the deaths of two young colleagues.

Neither of them had to look to others to understand substance abuse’s destructive power; they both experienced it firsthand. In Mickey’s case, it came in the proverbial, but all too real, form of hitting rock bottom. “I lost my business—I had a very successful nightclub-dinner restaurant that I lost to alcohol and drug abuse,” he recalls. “I ended up being found in a hotel room surrounded by bottles, on the verge of death, and had to have my heart jumpstarted in the emergency room.” Not even that–nor the doctor who outlined very precisely what lay ahead for him if he didn’t change his ways–was quite enough; after not drinking for 3 weeks he landed in a mental hospital in a straightjacket.

Mickey was 30 years old when he finally went sober with the help of AA, an organization and an approach in which he still strongly believes. But he did encounter some turbulence because, he says, AA tells alcoholics they have to get out of the restaurant business. “I must have heard that 100 times at the beginning of my sobriety,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Fuck you. You’ve taken away my drugs and you’ve taken away my alcohol, my two best friends. Now you want to take away the only other thing I love, which is hospitality?’ Forget it.”

He did give up the nightclub business, but switched to fine dining instead. He would spend the next forty years of his career there, at the acclaimed restaurants Tribute and The Charleston Grill, where he earned accolades as one of the US’s best maitre d’s, and the love of his colleagues and community for his warmth, care, and humanitarian work.

He knows, then, that with the right kind of support, it’s possible to stay in the industry and stay sober. Ben’s Friends is built on that idea: it’s a community that holds regular meetings–both in person and on Zoom— for people in the restaurant business. In addition to general meetings designed to give cooks, servers, bartenders, and somms the support they need with their sobriety, the organization also offers specialized sessions tailored to specific industry issues. In fact, they have a Zoom meeting coming up on Sept 22 entitled “Going Back to Work Sober in Bars and Restaurants.”

Still, Mickey knows all too well how daunting that prospect can be, and how it can even keep people from getting the help they need. ‘Everyone wonders, how can I be behind the bar and laugh and joke with my customers? How can I be a great server or sommelier if I don’t drink? But when you get to the point when you come in and look for help, the reality is you have never gone on a date sober, you’ve never gone out to dinner with friends, sober, you’ve never had sex, sober, you’ve never you’ve never gone bowling sober. It’s not specific to how am I going to work in the restaurant? It’s specific to, how am I going to live?”

He himself learned it helped to focus on what he would lose if he continued to drink, and to think of the alcohol itself as something that wanted to kill him. But most important of all was learning to rely on others. That included, most significantly, talking on a daily basis with someone else who was staying sober. And it meant being open at work. “AA is about anonymity. But in the restaurant world, it may not work to keep things anonymous. When I went back into the restaurants, I had to tell everybody that I was not drinking. That I could die from it. That they should please not ask me if I wanted a drink.”

That’s something that Ferhat Dirik, now sober for over two months, is discovering for himself. “The whole service aspect is inundated with cocktails, wine, beer. You’re surrounded by it. Shift drinks, or customers who might buy you a drink if you’re front of house like me. There’s all the wine tastings and samplings—I keep getting invited to wine trade events, and I have to respond to each one, and tell them I’m not drinking. It’s hard for people to remember that and be mindful of it.”

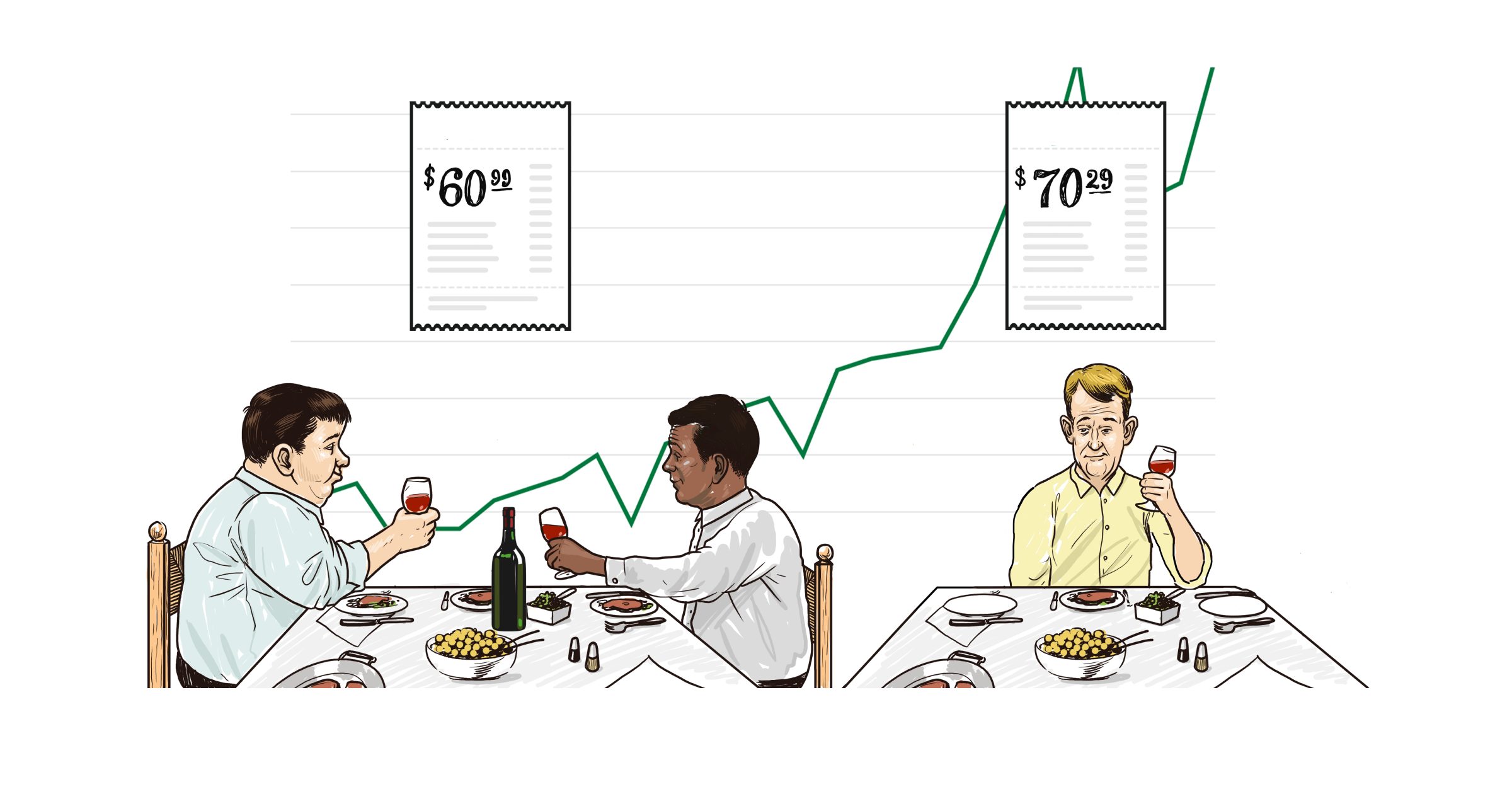

Still, in his newly sober state, he, like Mickey, is noticing some broader changes in the industry. “There’s more focus on alcohol-free offerings, more ferments, more shrubs, and as a restaurant, we’ve also picked up on a drop-off in wine sales.” And if response to his newsletter is any indication, more people in the industry are also trying to shift the culture away from focusing so heavily on drinking. “There’s a shift there,” he says. “It’ll be interesting to see how things develop.”

As for his own shift, by taking the step of writing openly and vulnerably about his decision to stop drinking—and then sending it out to everyone on Mangal 2’s mailing list—Ferhat is trying to hold himself accountable. “Accepting that I was an alcoholic was the hardest part, and then deciding to quit was hard. To cross those two bridges, the rest seems okay,” he says. “I’m just trying to take it one day at a time.”